Sunset in the Kettle Moraine Forest

Blue Moon: What the Discovery of Water on the Moon Means for the Possibility of Lunar Life

On October 26th, 2020 NASA announced that its Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA) discovered water for the first time on the sunlit surface of the Moon. This is not the first time water has been detected on the Moon. A Soviet probe took samples from the Moon in 1976 that contained 0.1% water by mass[i].

Nevertheless, the announcement stirred up a great deal of excitement in the scientific community, particularly among astrobiologists. On Earth, microorganisms are found virtually everywhere there is water, even in environments considered deeply inhospitable to life[ii]. This has led many astrobiologists to speculate that water is the most important ingredient in life. Although those of us eagerly anticipating the discovery of extraterrestrial life will be disappointed to learn that life on the Moon is still an extremely remote possibility, the discovery of water on the Moon could yield important information about how water is created and how it can persist in a variety of environments.

Life is an extremely hard concept to define. There is no single characteristic of an organism that defines it as being “alive.” Instead, there is a set of characteristics that are considered properties of life. These properties include:

- The ability to take in energy

- The ability to grow

- The ability to reproduce

- The ability to adapt to the environment.

The exact definition of life is more complicated and fiercely debated, because inorganic objects, such as crystals, possess some of the same properties[iii].

Life on Earth consists of membrane-bound, water-filled cells. Within these cells, energy obtained from the environment drives chemical reactions that allow cells to grow and reproduce. Water is a vital part of life because it is the chemical solvent in which these reactions occur.

A solvent is necessary because chemical reactions can only occur if the reactants are able to make contact with each other. Chemicals dissolved in a solvent are more likely to make contact with each other than chemicals freely floating in the air. Water is considered an ideal solvent for life because it exists as a liquid over a wide range of temperatures. It is also able to dissolve salts that contain ions which are important to life on Earth, including potassium, sodium, and chlorine[iv].

Theoretically, life on other planets could use another liquid as a solvent. Ammonia and hydrofluoric acid are considered distinct possibilities. But since no lifeform has been found that uses ammonia or hydrofluoric acid as a solvent, this remains pure speculation[v].

Despite the presence of water, the Moon is an unlikely host for life because it lacks the “chemical building blocks” of life. On Earth, the elements required for the building blocks of life are

- Carbon

- Hydrogen

- Nitrogen

- Oxygen

- Phosphorous

- Sulfur

Although the Moon contains all of these elements (oxygen is particularly plentiful), there are only trace amounts of carbon and nitrogen. It is possible that life on the Moon could use different elements as building blocks. Silicon, for example, has many of the same properties as carbon. However, silicon forms extremely strong bonds with oxygen, making it chemically inert. Life requires stable bonds that are weak enough to be chemically active. It is difficult to imagine silicon-based life evolving in an environment rich with oxygen. In fact, roughly half of the oxygen found on the Moon is trapped in silica (SiO2)[vi].

So, there is likely no native life on the Moon. But could we use the water found there to grow plants and hydrate a small colony?

Even this seems out of reach. The concentration of water found by NASA was only 100 to 412 parts per million. By comparison, the Sahara Desert has a 100x greater concentration of water. It seems unlikely that this tiny amount of water could sustain plant growth, even if we had a perfect waste-water filtration system.

Additionally, there are serious questions about the ability of plant life to thrive in low gravity environments. The gravitational pull of the Earth is an important factor in plant growth. The leaves of plants grow in the direction of sunlight, but the roots of plants grow in the direction of gravitational pull. Although experiments in growing plants on the International Space Station seem to indicate that plants, with a little bit of guidance, grow just fine in low gravity environments, there are warning signs at the genetic level that plants might struggle to survive and reproduce in low gravity.

Analyses of the mRNA sequences produced by Arabidopsis thaliana plants (the “lab rats” of botany) grown on the International Space Station show that plants grown in space produce proteins typically found in response to the build-up of reactive oxygen species, a chemical that causes damage to DNA. They also produce proteins associated with nearly every stress response system the plant has, from proteins produced by plants undergoing drought to proteins produced by plants undergoing flooding. At the genetic level, it appears that something about spaceflight is driving the plant haywire, but this doesn’t seem to impact its ability to grow normally[vii]. Perhaps low gravity doesn’t affect plant growth, but it’s also possible that there is something deeply wrong with the plant that may not be immediately noticeable. There just isn’t enough research to know for sure.

All life on Earth has evolved under roughly the same gravitational conditions for at least 3.5 billion years[viii]. It shouldn’t surprise us if Earth-based life struggles to adapt to even modest differences in gravitational force.

I know this article seems pessimistic. I’ve discounted the possibility of life on the Moon. I’ve questioned the feasibility of a colony on the Moon. I’ve even presented some daunting challenges facing long-term colonization of ANY place outside planet Earth. But I believe that we should not give up in the face of these challenges. Instead, we should use these challenges to push our imagination forward, because overcoming these challenges will require innovations that would take humanity beyond what it has ever dreamed possible.

-Erik Schwerdtfeger

[i] Akhmanova, M; Dement’ev, B; Markov, M (1978). “Possible Water in Luna 24 Regolith from the Sea of Crises.” Geochemistry International. 15 (166).

[ii] Cockell, CS (2015). Astrobiology: Understanding Life in the Universe. Wiley Blackwell. (124-138).

[iii] Schulze-Makuch, D, and Irwin, LN (2008). Life in the Universe: Expectations and Constraints. Springer. (7-12).

[iv] Cockell, (43-44).

[v] Ibid. (47-48).

[vi] Taylor, SR. (1975). Lunar Science: A Post-Apollo View. Pergamon Press. (64).

[vii] Barker, R, et al. (2020) “Test of Arabidopsis Space Transcriptome: A Discovery Environment to Explore Multiple Plant Biology Spaceflight Experiments.” Frontiers in Plant Science. 11

[viii] Cowen, R. (2013). History of Life. Wiley-Blackwell. (22).

Bridge Over Green Bay

Identity and Costume: A Look at Bo Bartlett’s Halloween

I hadn’t intended to write anything today, but a painting popped up on my Twitter feed this morning that I found so compelling, that I wanted to quickly share some thoughts on it.

Halloween is a 2016 oil painting by the American realist painter Bo Bartlett. The most striking element of the painting is the subject, a child dressed as a ghost, staring at the viewer with a harrowing and hypnotic look in his eyes. This child’s costume is more ambiguous than the rest of the children’s. The billowing sheet and thick face paint obscures even their gender identity, creating a sense of total anonymity.

This anonymity is accentuated by the desolate background, in which a cloudless sky generates an oppressive amount of negative space. While we can definitively place the setting of Halloween to somewhere in rural America, its specific location is ambiguous. This scene could be taking place anywhere from the desert West to the Great Plains to the farmlands of the American Midwest and South.

What this sense of ambiguity and anonymity highlights is the function of costumes. The use of a costume obscures our identity. Paradoxically, this anonymity allows us to express who we truly are. A costume allows us to express our desires and vulnerabilities without fear of identification. This is most evident in the subject of the painting, whose chilling look of loneliness and isolation is highlighted by the thick face paint surrounding their eyes.

We can also get a sense of the identity and desires of the other children, who are dressed as distinct cultural archetypes, from religious symbols such as an angel and a demon; to folklore in the wolf from Little Red Riding Hood and the witch, whimsically stepping just out of frame. There is even a contemporary cultural archetype in the Wonder Woman.

In the digital era, this sense of anonymity extends beyond Halloween and masquerades. We all have a sense of anonymity in our social media lives. In addition to allowing us to share our vulnerabilities, anonymity has also allowed us to indulge in our worse impulses without fear. Consider the “incel” phenomenon. What began as online groups of young men commiserating over their shared fears and insecurities soon exploded into violent anti-women extremism.

Perhaps there is a reason we only wear costumes on Halloween, a day marked by fear and mischief.

You can find more of Bo Bartlett’s work at https://www.bobartlett.com/

Seagulls Over Lake Michigan

Logic: Aristotelian vs. The School of Nyaya

With the United States presidential election just days away, we’re inundated with arguments and debates, as various candidates from both parties desperately pitch their ideas and ideologies in a final bid for votes. We are constantly bombarded with competing arguments, competing facts and figures, and even competing versions of reality. How can we sort through all this information and determine some sort of truth? That question has vexed philosophers for over two thousand years. It forms the basis of two branches of philosophy: logic and epistemology.

In the West, the works of the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle form the foundation of logic and epistemology. But philosophers in other ancient societies also formed equally sophisticated systems of logic and epistemology that are remarkably similar to Aristotle’s, but have distinctions that deserve to be considered in modern philosophy. In this article, we’ll examine the similarities and differences between the Aristotelian system of knowledge and the Hindu Nyaya school’s system of knowledge.

Aristotle was born in Macedonia in 385 BCE to the court physician of King Amyntas, the grandfather of Alexander the Great. After the death of his father in 367 BCE, Aristotle migrated to Athens, where he joined Plato’s Academy. He studied at Plato’s Academy, first as a student and then as a colleague, for 20 years, until the death of Plato in 347 BCE. Afterwards, he traveled across the Greek world. He helped found an academy in Assos, in modern day Turkey. He studied biology on the island of Lesbos. And he was hired by King Philip II of Macedonia to tutor his 13-year-old son, the future Alexander the Great[i]. In 335 BCE, he returned to Athens to found a new academy called the Lyceum. Although Aristotle would be forced to flee Athens following the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE, his students at the Lyceum continued to preserve, comment on, and expand upon his work for hundreds of years, cementing his legacy as one of Greece’s most prolific thinkers[ii].

Aristotle’s most influential work on logic is called Prior Analytics. In Prior Analytics, Aristotle establishes the theory of the syllogism. A syllogism is a set of premises that lead to a conclusion. For example,

- Every Greek is human.

- Every human is mortal.

- Therefore, every Greek is mortal.

Aristotle’s system of logic sets out to construct arguments in which the conclusion of the argument must be true if the premises are true. These are called valid arguments[iii]. Invalid arguments are arguments in which the conclusion is not necessarily true given the premise. For example,

- All Greeks are mortal.

- Anacharsis is mortal.

- Therefore, Anacharsis is Greek.

Just because all Greeks are mortal, it does not necessarily follow that all mortal things are Greek. This logical error is so common that it has its own name: affirming the consequent.

The most important thing to remember when considering Aristotle’s system of logic is that the conclusions are true ONLY if the premises are true. Thus, we cannot judge the truth of a conclusion without judging the truth of the premises. Still, Prior Analytics sets out a framework by which we can judge an argument based on its validity. While we cannot use Aristotle’s logic to definitively establish truth, we can use it to establish whether the premises of an argument can be used to justify the conclusion.

Little is known about the founding of the Nyaya school of philosophy. It is based upon the Nyaya Sutras, which were written by Aksapada Gautama, a philosopher who lived sometime between the 6th century BCE and 2nd century CE. The term “Nyaya” means “that by which the mind is led to a conclusion.” It is primarily concerned with the logic of arguments, and how those arguments can lead to the acquisition of knowledge. The Nyaya school’s system of logic is generally accepted by all major schools of Hindu thought, even in the heterodox traditions of Buddhism and Jainism[iv].

Each school of Hindu thought accepts the concept of karma. Although they differ in their specific views regarding the nature and consequences of karma, the general idea is that good things do not come from bad actions and vice versa. Thus, whether an action is ethical or not is judged by calculating the amount of suffering brought into the universe by the action versus the amount of suffering alleviated by the action. Under this ethical system, it is possible to commit unethical acts not out of evil intent, but out of pure ignorance. Because evil can result from ignorance, the acquisition of knowledge is about more than just sating our curiosity. Acquiring knowledge is itself a form of ethics.

The Nyaya school established a five-stage argument structure, in which a set of premises is given to support a conclusion (taken from Victoria S. Harrison, 2013):

- The premise to be established is stated

- The reason for the premise is given

- An example is provided

- The application of the example to the premise is explained

- The conclusion is stated

For example:

- There is a fire on this hill (premise established)

- Because there is smoke (reason given)

- Since whatever has smoke has fire, for example, an oven has smoke resulting from its fire (example provided)

- There is smoke on this hill, which is associated with fire (application)

- Therefore, there is a fire on this hill (conclusion)

Some argue that the Nyaya system of logic is reducible to an Aristotelian syllogism[v]. For example, we could restate the above argument as

- Wherever there is smoke, there is fire.

- There is smoke on this hill.

- Therefore, there is fire on this hill.

However, this reduction is missing a crucial element of Nyaya logic. Nyaya logic requires an example in order to establish the truth of the premises. Remember that Aristotelian logic can only establish whether the argument is valid, not whether the conclusion is true. By requiring an example to justify the truth of the premises, Nyaya logic attempts to establish that an argument is both valid and that the conclusion is true.

Logic is concerned with how to form arguments in such a way that the conclusion of the argument must be true. Epistemology is concerned with how to establish knowledge, whether from abstract arguments or from our sensory experiences. For example, consider the following argument:

- Only dogs bark.

- Jimmy barks.

- Therefore, Jimmy is a dog.

A logician would ask whether the premises “Only dogs bark” and “Jimmy barks” lead to the conclusion that Jimmy is a dog. An epistemologist would ask “Is it true that only dogs bark? Did Jimmy actually bark, or did he make a noise that sounds similar to a bark? What is a bark? How can I be certain that I actually heard Jimmy bark and that I didn’t experience an auditory hallucination of Jimmy barking?”

Clearly, an epistemologist has their work cut out for them. How can we be certain that our sensory experiences are representative of some underlying material truth? How can we justify the use of one observation (or many observations) to generalize about any future event? For example, if every dog I’ve ever met barked, does that necessarily mean that every dog in the universe barks? In philosophy, this is referred to as “the problem of induction.” As far as I know, no philosopher has ever come up with a conclusive solution to it.

Aristotle sidesteps the problem of induction by simply establishing validity, rather than by attempting to establish truth. The Nyaya school, on the other hand, dives headfirst into the problem of induction by attempting to establish the validity of the argument and the truth of the conclusion. However, the Nyaya school does not solve the problem of induction because an argument can be entirely valid within their argument structure, but still produce a false conclusion. For example, consider this argument

- A dolphin gives birth on land

- Because a dolphin is a mammal.

- Since all mammals give birth on land. For example, a bear is a mammal and a bear gives birth on land.

- A dolphin is a mammal, which is associated with giving birth on land.

- Therefore, a dolphin gives birth on land

This argument fails to establish a true conclusion because the premise that all mammals give birth on land is not true. The premise “all mammals give birth on land” cannot be established as true because the example of a bear giving birth on land cannot be generalized to all mammals.

The structure of arguments in modern science is similiar to the Nyaya school of philosophy. Scientists construct arguments that must be valid, and they support the premises of those arguments with experimental data (examples). But the problem of induction remains. For example, say I perform an experiment which finds that corn plants grow better when given one liter of water a day compared to corn plants that receive a half liter of water a day. Can I generalize that example to conclude that all corn plants grow better when given a liter of water a day?

Instead of solving the problem of induction, modern scientists attempt to alleviate the problem of induction. Rather than attempting to conclusively prove the truth of their argument, they provide examples as evidence of the truth of their argument. They then challenge others to find a counterexample that proves their experimental observations cannot be generalized. This concept, called falsificationism, was expounded on by the 20th century philosopher Karl Popper[vi].

The point of comparative philosophy is not to conclusively prove that one system of philosophy is objectively “better” than another. Instead, by examining the ways in which different philosophers from different parts of the world have thought about the same problems, we can think about these problems in deeper and more nuanced ways.

People are often extolled to “think logically” or “think rationally.” While thinking logically is an undeniably good thing, it’s important to remember that just because we come to a logical conclusion, it does not necessarily mean that this logical conclusion is “correct.” The Nyaya school of thought drives that point home by demanding that the argument not just come to a logical conclusion, but justify the premises that led to that conclusion.

With a major election just around the corner, now is a great time to take stock of our own beliefs. Are the arguments in support of your political beliefs valid? Can you justify the premises of your arguments? These questions are worth asking. Our society faces many deep and urgent problems. How can we solve climate change? How can we safeguard privacy and liberty in the era of Big Data? How can we build a society that is both prosperous and equitable? I believe if more people think more deeply about these problems, we have a better chance of finding and implementing solutions.

-Erik Schwerdtfeger

[i] Anthony Kenny. A New History of Western Philosophy Volume 1: Ancient Philosophy. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004). 65-73.

[ii] Richard McKeon. The Basic Works of Aristotle. (New York: Random House, 2001).

[iii] Anthony Kenny, 2004. 117-120.

[iv] Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan and Charles A. Moore. A Sourcebook in Indian Philosophy. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1967). 356.

[v] Victoria S. Harrison. Eastern Philosophy: The Basics. (New York: Routledge, 2013).

[vi] Peter Godfrey-Smith. Theory and Reality. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003). 57-61.

The Biochemistry of Autumn

It’s hard not to think about death on a cool October day. Ghosts and ghouls decorate houses in anticipation of Halloween. Dead leaves crunch beneath your feet. The earthy scent of autumn wafts in the brisk wind. The forest seems to glow with red, orange, and golden leaves whispering in the breeze before falling, forming a thick mat of death upon the forest floor.

At least, that’s what October is like at my home in Wisconsin, which lies in the heart of North America’s deciduous forests. Deciduous forests are marked by their warm, wet summers and freezing cold winters. This climate cycle produces summers that are highly productive for plant life, but also produces highly stressful winters which stifle plant growth. This cycling between productive summers and challenging winters drives the leaf fall that defines deciduous forests[i]. In fact, autumn is not a season of death, but a testament to life’s tremendous ability to endure.

Plant growth is less productive during the winter because the lower temperature results in frozen surface water. This prevents plants from absorbing water through their roots. Water is an essential part of all known life. In plants, water serves the same purpose as blood (which is ~92% water) in animals. It carries nutrients, chemical signals, and various proteins across the plant through a vascular system. Plants require water for more than just hydration. Except for carbon and oxygen, plants also receive all their nutrients through their roots.

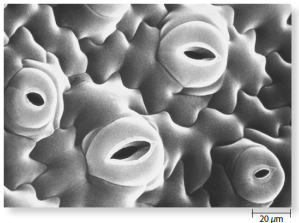

When freezing weather makes water uptake difficult, it is crucial for the plant to avoid water loss. That’s where leaf fall comes in handy. Leaves contain tiny pores called stomata. Stomata allow plants to take in carbon dioxide and expel oxygen. Essentially, stomata allow the plant to “breathe.” Unfortunately, stomata also allow water to escape the plant as water vapor. Deciduous trees prevent water loss by shedding their leaves in the fall. This allows deciduous trees to sustain themselves by preventing water loss, but at the cost of losing their photosynthetic capabilities[ii].

If leaf fall is what allows deciduous trees to survive the winter, why don’t the evergreen coniferous trees farther north lose their leaves? The answer lies in the structure of the pine needle. Pine needles have less stomata and a thick, waxy substance called a cuticle covering them. This prevents water loss through the stomata, allowing the plant to retain enough water to continue photosynthesis, even during freezing weather.

But if coniferous trees are able to continue photosynthesis during freezing weather, why aren’t all trees in freezing climates coniferous? Why have deciduous trees at all?

The ability of coniferous trees to continue photosynthesis in freezing temperatures comes at a cost. Pine needles cannot absorb as much sunlight as broadleaf deciduous trees because the conical pine needles have less surface area than broadleaf leaves. Additionally, the waxy coating on pine needles that prevents water loss also hampers gas exchange. Essentially, the wax makes it harder for the tree to “breathe.”

Therefore, coniferous trees are generally less efficient than deciduous broadleaf trees, but are able to continue photosynthesis in winter. Deciduous trees are more efficient than coniferous trees, but are unable to perform photosynthesis in winter. In the north, where freezing weather lasts longer, coniferous trees have the advantage and dominate the landscape. And in the more temperate south, deciduous trees have the advantage and dominate the landscape.

The bright orange, red, and gold colors that dominate the autumn forests are a result of the other consequence of freezing water: nutrient deficiency.

Nitrogen is an essential nutrient in plants. It is a vital component of proteins, nucleic acids, and chlorophyll. Lack of nitrogen is the main limitation on plant growth. In fact, the development of industrially produced nitrogen in 1914 led to modern agricultural fertilizers, without which the planet could not sustain the current population[iii].

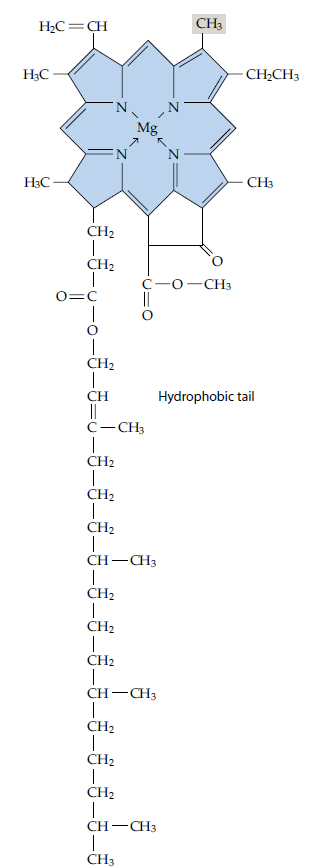

Nitrogen is an important component of chlorophyll, a chemical found in chloroplasts. Chlorophyll molecules are responsible for “catching” light photons, which the rest of the chloroplast uses to produce energy[iv].

When trees lose their leaves, the leaves do not simply die. Instead, they go through a process called senescence in which chlorophyll is broken down so that the nitrogen can be extracted and preserved. Chlorophyll causes the vibrant green color we associate with plants. When chlorophyll is lost, the leaf loses its green color and the colors produced by other chemicals in the leaves, such as carotenoids and anthocyanins, become visible. Carotenoids and anthocyanins are also responsible for the bright color of carrots, tomatoes, bell peppers, etc[v].

Carotenoids and anthocyanins are also broken down, but at a slower pace than chlorophyll. That’s why when leaves finally fall, they are usually pale brown.

But how do trees know when to lose their leaves? Trees don’t have a brain or nervous system. They don’t have the capacity to consciously “feel” when winter is coming. The exact mechanism varies based on the species of tree, but generally, the changing length of day and cooling temperatures trigger chemical signals that lead the plant to begin the process of senescence[vi].

The changing of the seasons has long been interpreted as a metaphor for the circle of life, with the fall of the leaves symbolizing death and the budding of new leaves symbolizing birth. In fact, leaf fall is not a sign of death, but an innovative adaptation that allows trees to survive and thrive under deeply challenging conditions. Don’t think of a tree stripped bare of its leaves as a symbol of death and desolation. Instead, see it as a symbol of endurance.

Autumn is a remarkable tribute to the ability of life to endure, which I find especially poignant in 2020, a year marked by pandemic, economic devastation, and violent police repression. Just as a tree endures the winter, I believe we shall endure this and bloom brighter than ever.

[i] Lisa A. Urry, et al. Campbell Biology. (New York: Pearson Education, 2017), 1174.

[ii] Ray F. Evert and Susan E. Eichhorn. Raven Biology of Plants. (New York: W.H. Freeman and Company, 2013), 7.

[iii] Ibid. 692, 699.

[iv] Ibid. 126-129.

[v] Howard Thomas, et al. “Senescence and Cell Death.” Biochemistry & Molecular Biology of Plants. Ed. Bob B. Buchanan, Wilhelm Gruissem, and Russel L. Jones. (Oxford: Wiley Blackwell. 2015). 950.

[vi] Lincoln Taiz and Eduardo Zeiger. Plant Physiology. (Sunderland: Sinauer Associates, 2010). 370.