It’s hard not to think about death on a cool October day. Ghosts and ghouls decorate houses in anticipation of Halloween. Dead leaves crunch beneath your feet. The earthy scent of autumn wafts in the brisk wind. The forest seems to glow with red, orange, and golden leaves whispering in the breeze before falling, forming a thick mat of death upon the forest floor.

At least, that’s what October is like at my home in Wisconsin, which lies in the heart of North America’s deciduous forests. Deciduous forests are marked by their warm, wet summers and freezing cold winters. This climate cycle produces summers that are highly productive for plant life, but also produces highly stressful winters which stifle plant growth. This cycling between productive summers and challenging winters drives the leaf fall that defines deciduous forests[i]. In fact, autumn is not a season of death, but a testament to life’s tremendous ability to endure.

Plant growth is less productive during the winter because the lower temperature results in frozen surface water. This prevents plants from absorbing water through their roots. Water is an essential part of all known life. In plants, water serves the same purpose as blood (which is ~92% water) in animals. It carries nutrients, chemical signals, and various proteins across the plant through a vascular system. Plants require water for more than just hydration. Except for carbon and oxygen, plants also receive all their nutrients through their roots.

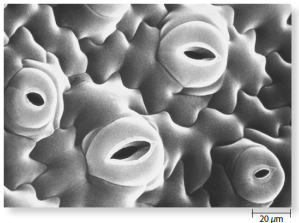

When freezing weather makes water uptake difficult, it is crucial for the plant to avoid water loss. That’s where leaf fall comes in handy. Leaves contain tiny pores called stomata. Stomata allow plants to take in carbon dioxide and expel oxygen. Essentially, stomata allow the plant to “breathe.” Unfortunately, stomata also allow water to escape the plant as water vapor. Deciduous trees prevent water loss by shedding their leaves in the fall. This allows deciduous trees to sustain themselves by preventing water loss, but at the cost of losing their photosynthetic capabilities[ii].

If leaf fall is what allows deciduous trees to survive the winter, why don’t the evergreen coniferous trees farther north lose their leaves? The answer lies in the structure of the pine needle. Pine needles have less stomata and a thick, waxy substance called a cuticle covering them. This prevents water loss through the stomata, allowing the plant to retain enough water to continue photosynthesis, even during freezing weather.

But if coniferous trees are able to continue photosynthesis during freezing weather, why aren’t all trees in freezing climates coniferous? Why have deciduous trees at all?

The ability of coniferous trees to continue photosynthesis in freezing temperatures comes at a cost. Pine needles cannot absorb as much sunlight as broadleaf deciduous trees because the conical pine needles have less surface area than broadleaf leaves. Additionally, the waxy coating on pine needles that prevents water loss also hampers gas exchange. Essentially, the wax makes it harder for the tree to “breathe.”

Therefore, coniferous trees are generally less efficient than deciduous broadleaf trees, but are able to continue photosynthesis in winter. Deciduous trees are more efficient than coniferous trees, but are unable to perform photosynthesis in winter. In the north, where freezing weather lasts longer, coniferous trees have the advantage and dominate the landscape. And in the more temperate south, deciduous trees have the advantage and dominate the landscape.

The bright orange, red, and gold colors that dominate the autumn forests are a result of the other consequence of freezing water: nutrient deficiency.

Nitrogen is an essential nutrient in plants. It is a vital component of proteins, nucleic acids, and chlorophyll. Lack of nitrogen is the main limitation on plant growth. In fact, the development of industrially produced nitrogen in 1914 led to modern agricultural fertilizers, without which the planet could not sustain the current population[iii].

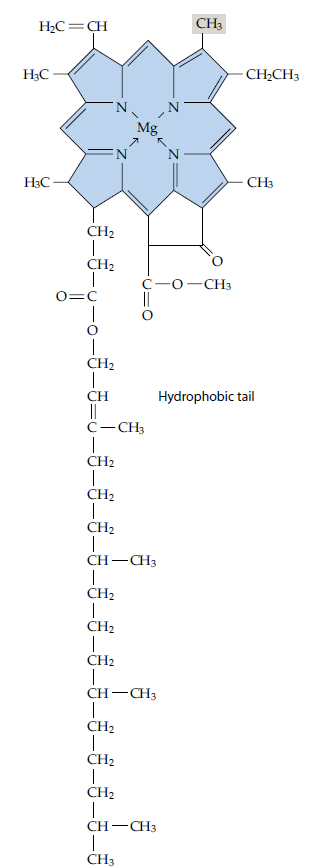

Nitrogen is an important component of chlorophyll, a chemical found in chloroplasts. Chlorophyll molecules are responsible for “catching” light photons, which the rest of the chloroplast uses to produce energy[iv].

When trees lose their leaves, the leaves do not simply die. Instead, they go through a process called senescence in which chlorophyll is broken down so that the nitrogen can be extracted and preserved. Chlorophyll causes the vibrant green color we associate with plants. When chlorophyll is lost, the leaf loses its green color and the colors produced by other chemicals in the leaves, such as carotenoids and anthocyanins, become visible. Carotenoids and anthocyanins are also responsible for the bright color of carrots, tomatoes, bell peppers, etc[v].

Carotenoids and anthocyanins are also broken down, but at a slower pace than chlorophyll. That’s why when leaves finally fall, they are usually pale brown.

But how do trees know when to lose their leaves? Trees don’t have a brain or nervous system. They don’t have the capacity to consciously “feel” when winter is coming. The exact mechanism varies based on the species of tree, but generally, the changing length of day and cooling temperatures trigger chemical signals that lead the plant to begin the process of senescence[vi].

The changing of the seasons has long been interpreted as a metaphor for the circle of life, with the fall of the leaves symbolizing death and the budding of new leaves symbolizing birth. In fact, leaf fall is not a sign of death, but an innovative adaptation that allows trees to survive and thrive under deeply challenging conditions. Don’t think of a tree stripped bare of its leaves as a symbol of death and desolation. Instead, see it as a symbol of endurance.

Autumn is a remarkable tribute to the ability of life to endure, which I find especially poignant in 2020, a year marked by pandemic, economic devastation, and violent police repression. Just as a tree endures the winter, I believe we shall endure this and bloom brighter than ever.

[i] Lisa A. Urry, et al. Campbell Biology. (New York: Pearson Education, 2017), 1174.

[ii] Ray F. Evert and Susan E. Eichhorn. Raven Biology of Plants. (New York: W.H. Freeman and Company, 2013), 7.

[iii] Ibid. 692, 699.

[iv] Ibid. 126-129.

[v] Howard Thomas, et al. “Senescence and Cell Death.” Biochemistry & Molecular Biology of Plants. Ed. Bob B. Buchanan, Wilhelm Gruissem, and Russel L. Jones. (Oxford: Wiley Blackwell. 2015). 950.

[vi] Lincoln Taiz and Eduardo Zeiger. Plant Physiology. (Sunderland: Sinauer Associates, 2010). 370.